Christmas Trees in WPF, 2016 Edition

Last year, I wrote about making Christmas Trees in WPF using FSharp.ViewModule.  At the time, I was excited being able to demonstrate how FSharp.ViewModule could make typical MVVM much more functional feeling.  This year, for my F# Advent Calendar contribution, I want to demonstrate how Gjallarhorn.Binding can serve as a replacement, and help create a WPF application with a design that is clean, functional, and most importantly, simple.

This post will modernize the Christmas Tree application from last year, improving it, and highlighting the differences between a classic MVVM approach to WPF and a more functional approach.  While reading through the post from last year would add context, it’s completely optional.

As always, I’ll begin with a brief introduction to the model. Â I’ve taken the model from last year mostly as-is, except simplified it and made it more “idiomatic F#”. Â This year, I broke out the model for a Tree into its own file:

The actual Tree type is unchanged – but I’ve created the functions to create a new tree and update an existing tree, and placed them into a module for working with trees. Â This isolates the types and logic for dealing with a single tree into its own testable portion of the application, and is simple, easy to follow, and easily extensible.

The model for a Forest has received similar treatment:

The main differences when compared to the version from last year is that the logic is now contained in a module, and the message type for updating a forest is dramatically simplified, and now has three options – it can add a new tree, given a location, prune the existing forest if it’s larger than a given size, and update a tree given a TreeMessage and a Tree.  The logic for these just calls into the Tree module when appropriate, making this far easier to understand and extend in the future.

The code up to this point is completely “pure F#” – no external libraries are required, and everything is self contained, testable, immutable, and easy to reason about.  I have a Forest comprised of a list of Tree records, with functions performing updates that returning a new Forest.

Up to this point, what I have is very similar to what I had last year, just slightly more organized, with the Tree having its own module isolating its own logic.

However, this is where things start to change.  In order to wire this up to a UI, there are a few options.

I could go with a naive, just “build out the controls and wire up everything in code” style. Â This would work, but tends to lead to a mess of spaghetti, lots of brittle event handling for changing the views and pushing back state, and other issues. Â It becomes even more of a mess when considering the fact that the model is represented by a collection – hand-wiring events for managing collections is difficult to get correct, and typically requires a lot of code.

I could go with a classic MVVM approach: this would likely require making a “view model” class to represent a forest and another to represent tree, adding logic in the tree for whether it should be decorated, and adding some mechanism, typically either custom events or a messaging service, to notify the main view model that a tree is updated, wiring up the logic to map to and from the (immutable) model classes, and the like.  Realistically, the boilerplate required to do this would be far more code than I’ve written for the actual application so far – with the collections becoming the most difficult aspect.  Libraries like ReactiveUI or DynamicData can simplify this, but it still is effectively copying the model (manually) into a custom collection of view models, managing them, and manually constructing the model back from the results.

My approach last year was to use FSharp.ViewModule’s EventViewModelBase and custom converters to manage some of this complexity.  That worked quite well – and I was happy (mostly) with the approach, but even so, I ended up creating a custom view model class, two MailboxProcessors to manage synchronization, and a lot of care had to be taken to make sure to always marshal back onto the UI thread before touching the collection (or you get exceptions from WPF) and similar “gotchas” that really are completely separate concerns from my core logic.  At its core this approach still uses an MVVM philosophy for its architecture, though it has a much more functional slant which does help tame some of the complexity.

MVVM, while the most common architectural pattern for dealing with WPF, has some fundamental flaws. Â At its core, MVVM is about isolating the view and using data binding to wire up changes to a “view model”, where the changes edit properties, and then the view model takes on the requirements of updating the model. Â I’ve written about MVVM in detail, and used it quite a bit, but there are a few annoying aspects:

- Everything is based on mutation. Â By definition, the View Model layer is going to be mutable, as edits work via (two way) data binding that set values on the properties.

- There’s a lot of boilerplate involved – every view typically ends up needing a complete class written for it to manage its state and logic.

- It can be difficult to reason about, especially when collections are involved.

- The “plumbing” requirements to keep updates within collections can become onerous quickly. Â This tends to lead to inappropriate changes being made to the Model, as evidenced by the common arguments like “it’s just easier if I make this model mutable and implement INotifyPropertyChanged”. Â Over time, this can make the application far more complex, introduce bugs, and cause a myriad of other problems.

That being said, MVVM does bring some concrete benefits:

- The View stays very isolated, and can be changed without changing the application logic and code at all.

- The Model can be kept “pure”, which allows for easy reuse of the core code in other platforms (though, in practice, this is often broken – see above).

This year, I’ve decided to go with a completely different approach.

At the beginning of 2016, I started playing with ideas of how to break some of the underlying expectations when building WPF (and other data binding based) applications.  This centered around a couple of ideas - rethinking data binding to eliminate mutation at its core and eliminating the need to create classes to make data binding work.  This has evolved into the Gjallarhorn.Binding project, built on top of Gjallarhorn.

In order to build a UI with Gjallarhorn, instead of making classes to support data binding, I create some simple functions, referred to as a “Component” in Gjallarhorn.Bindable.  A Component is defined as:

BindingSource -> ISignal<'TModel> -> IObservable<'TMessage> list

The BindingSource type is defined in Gjallarhorn.Bindable, and used to map the model to the view, and events from the view back into messages.  The ISignal<‘a> interface is the core type in Gjallarhorn, and can be thought of as an IObservable<‘a> (which it inherits) that always contains a current value.  Gjallarhorn provides a full set of operations for working with signals, including mapping, merging, filtering, conversion to and from observables and other types, and more.  The Component for mapping the Tree to something usable by data binding is defined as:

This function takes the model (the ISignal<Tree>) and binds it directly “to the view” via the name “Tree”. Â This effectively creates a one-way “Tree property” the view can data bind into. Â I then create a “message source”, which WPF sees as an ICommand. Â The Binding.createMessage function returns an IObservable<‘a>. When the command is executed, it will output a Decorate message into the observable stream.

Similarly, IÂ create a Component to manage the Forest type as a whole:

This is slightly different – as the Forest is a sequence, I use BindingCollection.toView to bind the entire collection to the view, saying “for each item in the sequence (a Tree), use the treeComponent function to build out the binding for that element, and aggregate all of the messages from those into a single message stream that’s the original message and the individual tree as a tuple.  I then map this in the output stream into UpdateTree message types, and also create a command to add a new tree, which maps the command parameter into the argument of the Add DU case.

Finally, I build the application plumbing.  The one thing I’m not handling at this point is pruning of the forest – which I want to just run continually.  For Gjallarhorn.Bindable, I need to create three functions for the application – a function to create the initial model (the Forest), an init function that runs one time after all of the contexts have been setup, and an update function for the top level model.  These are passed into the Framework.application function, along with the main component, which builds out the “logical application”:

At this point, I have the underlying logic for the entire application defined – and best of all, it’s defined in a portable class library that’s completely reusable as-is between WPF and other data binding platforms – I could use this same project, without changes, to build out a Xamarin Forms Android app, for example.

The WPF project just references this, pulls in FsXaml, and has two files. Â First, IÂ define the XAML for the View:

This looks very similar to the XAML from last year, except that I moved the Tree rendering into its own resource, and simplified the event handling.  I no longer need two converters – only a single converter is required (to go from clicking on the Canvas to a Location for adding a tree) – Gjallarhorn.Bindable takes care of mapping the ICommand to a Decorate message without any work being done in the View, but clicking on the Canvas and mapping to a location requires a converter to be written:

This converter is similar to the one last year – but I’m taking advantage of a newer FsXaml feature that allows us to convert to an option and filter out None results automatically.

Once that’s done, I load the XAML using the FsXaml type provider, and the application entry point becomes nothing but having the WPF specific portion of Gjallarhorn (from the Gjallarhorn.Bindable.Wpf reference) launch the application.  This just requires a single function call – it takes a function to construct an Application (in this case, I’m using the default WPF application), the main Window (from the type provider), and the application from the portable class library:

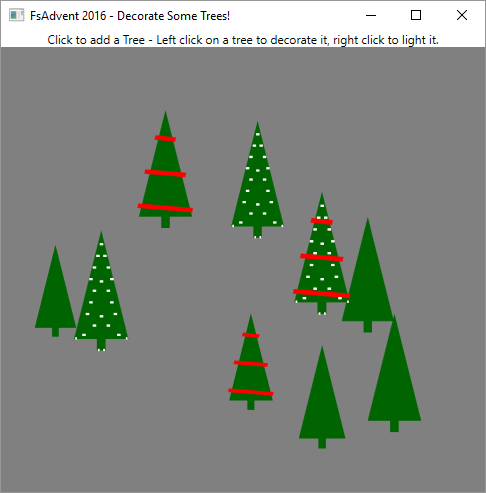

That’s it – the entire application.  Every line of source code (other than namespace definitions and open statements) is included.  When I run, I get an improved version of what I had last year.  I can click on the window to add trees, and click on a tree to decorate them.  The main improvement is in the pruning behavior – if I add more than 10 trees, I start to see some disappear one at a time every half second, using some randomness that didn’t exist in the previous version.

I’d like to point out some differences here when compared to last year – The model is completely immutable and pure.  The entire application state is defined in one place, and easily managed.  I just need to provide a mechanism to turn it into a signal (to monitor changes) and to update.  Nowhere in this application do I worry about threading or synchronization, even though the pruning is happening in background threads asynchronously.  I don’t create a single “view model” class for data binding, rather just define simple functions that map from my model to binding targets, and route messages out.  The entire application is simple, easy to reason about, and very clean.

In addition, this application is far easier to modify as requirements change. Â For fun, I’m going to add some new functionality. Â In addition to decorating the tree, I’m going to add the ability to light a tree.

I’ll modify the Model to allow trees to be decorated and lit. This requires changing the Tree record, adding a new Light message, and modifying the update function:

Now I need to add another command to the tree component which generates Light messages:

Finally, I need to tweak the XAML slightly. Â It needs two changes – a way to trigger the new command (I’ll use right mouse to light the tree), and the actual rendering of the lights as another path. Â First, IÂ put in the right mouse click EventToCommand:

And then IÂ add a new path for the lights (full xaml not shown), and update the instructions:

Now, when I run, I can light and decorate the trees!

This required no major changes to plumbing – I wanted to update how trees work, so a simple addition to the Tree model, and a couple of lines of code, and I’m done. Â The entire set of changes required to add lighting is trivial, and can be seen in this GitHub commit.

As always, I’ve put the code on GitHub, so please download, try it out, and enjoy!

And remember to enjoy the rest of the F# content in the 2016 F# Advent Calendar!

Update on Dec 16th: A new “blinking” branch of the repository has been created, showing off submitted improvements, such as making the lights blink on and off!  Definitely worth trying the original and the improved versions.  Thank you Gene Chiaramonte (@waahhoo) and family!

Hi,

I’m trying to adopt this approach in my little application, but I’m facing some “issues” which I can’t figure out how to solve properly.

In your case you have model’s default value Forest.empty and use it as the initial model value wrapped in AsyncMutable. All is good, since it’s a proper state of the model – empty list of Trees.

In my case I have a type which is similar to this one:

type MyModel = {

EmailAddress: EmailAddress.T

Title: string

}

Where EmailAddress.T can be created by special “create” function which returns Result:

module EmailAddress=

type T = EmailAddress of string

let create (email:string) =

//… check email

if validEmail then

Ok (EmailAddress email)

else

Error “Wrong email format”

This means that MyModel can’t have a nice default value (with EmailAddress empty), since EmailAddress field must have proper email, but I don’t want to set dump name there since the initial state of the model will be bound to WPF textboxes, and user should see empty text boxes upon start.

I might set Result as a initial state of the model, or I need to create anther type to hold just string properties which I will later convert to MyModel’s fields, I can’t figure out the proper way.

It looks like that with my approach I can’t nicely bind my model.

Is there a way to solve this? Maybe I can tweak something in the library or in my code?

Thanks in advance!

Best regards,

Kirill

Kirill,

I’d make your model’s initial state None, and have the model be an option. It’s easy to map signals of None to an empty string for binding. This matches the domain, as there effectively is “no real default” initial state.

I’d be happy to chat more if you have questions. I’d recommend F# Software Foundation’s slack – becoming a member is free, and it’s a great place to discuss.

-Reed

Thanks for your reply!

I’ll try Option as you suggested

Best regards,

Kirill

Thanks, this is super interesting!